Gallbladder mucocele (GBM) is one of those conditions that can quietly smolder for months—and then suddenly turn catastrophic. It is now a common hepatobiliary disease in dogs, frequently encountered in small animal practice, especially with the widespread use of abdominal ultrasound.

This article focuses on what matters clinically: recognition, interpretation, decision-making, and management.

What Is a Gallbladder Mucocele?

A gallbladder mucocele occurs when thick, immobile, mucus-rich bile accumulates within the gallbladder, gradually replacing normal liquid bile. Over time, this material becomes rubbery or gelatinous and fails to empty into the bile duct.

As pressure increases, the gallbladder wall becomes compromised, leading to:

- Ischemia

- Necrosis

- Rupture and bile peritonitis (often fatal if untreated)

GBM is therefore not just a liver issue—it is a surgical disease waiting to happen.

Why Does It Happen? (Pathophysiology)

The exact cause is multifactorial, but key mechanisms include:

- Abnormal bile composition (excess mucin production)

- Gallbladder dysmotility

- Hormonal influences

- Underlying metabolic disease

Common associations:

- Hyperadrenocorticism (Cushing’s disease)

- Hypothyroidism

- Hyperlipidemia

- Diabetes mellitus

Certain breeds appear predisposed:

- Shetland Sheepdog

- Cocker Spaniel

- Miniature Schnauzer

- Pomeranian

But importantly—any dog can develop a mucocele.

Clinical Signs: Often Subtle, Sometimes Sudden

Early or Incidental Cases

- Asymptomatic

- Mild ↑ ALT / ALP

- Detected incidentally on ultrasound

Progressive / Symptomatic Cases

- Vomiting

- Anorexia

- Lethargy

- Abdominal pain

- Icterus

- Pale or acholic stools

Emergency Presentation

- Acute collapse

- Severe abdominal pain

- Shock

- Septic peritonitis from gallbladder rupture

Clinical pearl:

A dog with vague GI signs + cholestatic enzymes deserves an ultrasound—don’t dismiss it as “gastritis.”

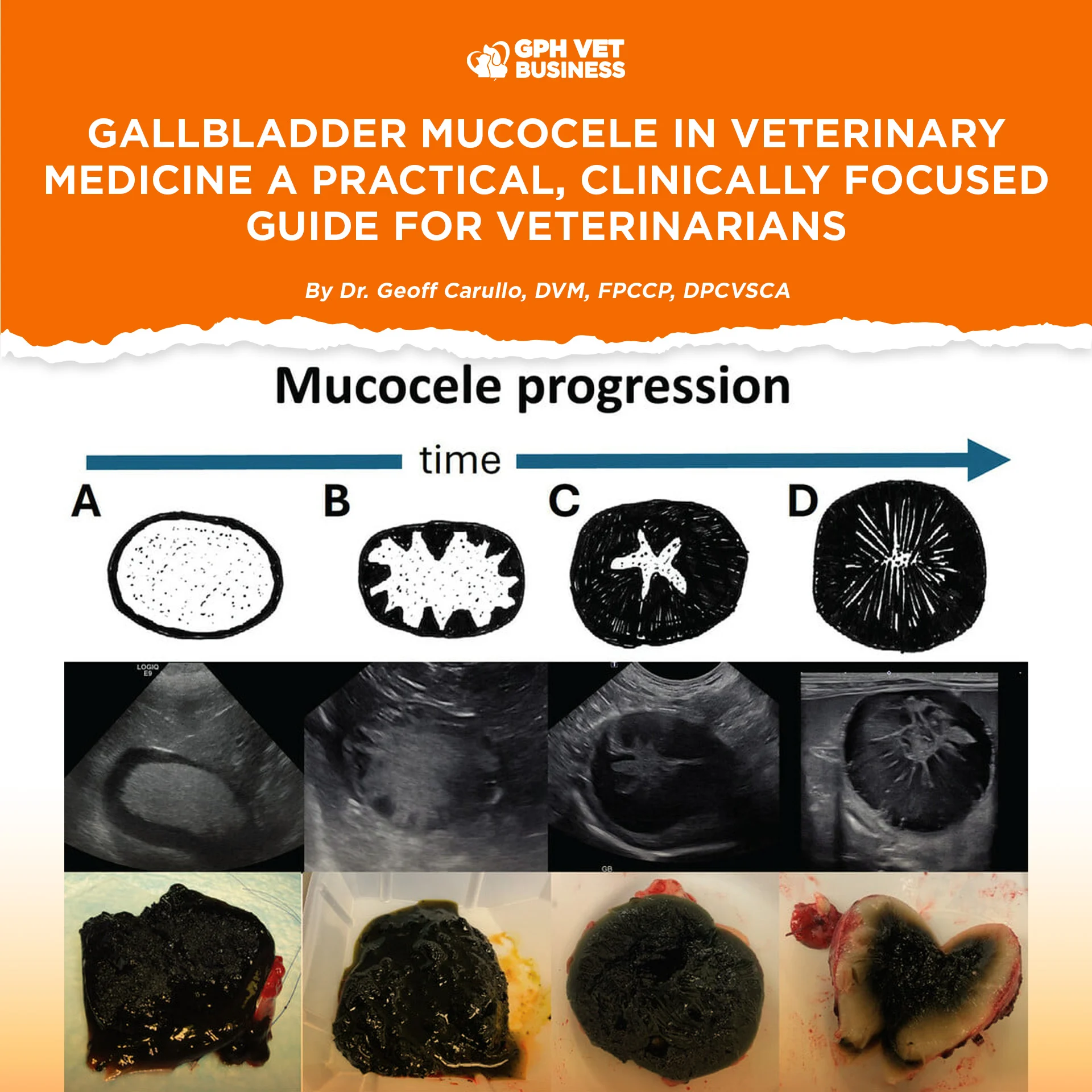

Diagnosis: Ultrasound Is King 👑

Classic Ultrasonographic Findings

- “Kiwi fruit” or stellate pattern

- Echogenic, immobile bile

- Distended gallbladder

- Thickened or hyperechoic gallbladder wall

- Pericholecystic fluid (red flag!)

Unlike biliary sludge, mucocele contents do not move with patient repositioning.

Laboratory Findings (Supportive, Not Diagnostic)

- ↑ ALP (often marked)

- ↑ ALT

- Hyperbilirubinemia (late-stage)

- Inflammatory leukogram if rupture/infection

Medical vs Surgical Management: The Critical Decision

Medical Management (Very Select Cases Only)

Consider ONLY if:

- Patient is asymptomatic

- Gallbladder wall intact

- No peritoneal effusion

- Owner is compliant with close monitoring

Medical options:

- Ursodeoxycholic acid

- Hepatoprotectants

- Low-fat diet

- Treat underlying endocrine disease

⚠️ Clinical reality:

Many dogs managed medically will eventually require surgery.

Surgical Management: Cholecystectomy

Cholecystectomy is the definitive treatment for symptomatic or high-risk GBM.

Indications for Surgery

- Clinical signs present

- Evidence of gallbladder wall compromise

- Rising bilirubin

- Pericholecystic fluid

- Suspected or confirmed rupture

Prognosis

- Good to excellent if performed before rupture

- Guarded to poor if bile peritonitis is present

Clinical pearl:

Timing matters more than technique. Early referral saves lives.

Post-Operative Considerations

- Monitor bile ducts intraoperatively

- Manage hypotension and sepsis aggressively

- Temporary post-op GI signs are common

- Long-term prognosis is usually excellent if patient survives surgery

Key Clinical Pearls (Take-Home Points)

- Gallbladder mucocele is common and increasing in incidence

- Ultrasound pattern recognition is crucial

- Many cases are silent until they rupture

- Medical management is limited and risky

- Early cholecystectomy = best outcome

- Delay kills—not the surgery

Final Thought

Gallbladder mucocele is a perfect example of a “looks stable today, crashes tomorrow” disease. As veterinarians, our job is not just to treat symptoms—but to recognize patterns early and act decisively.

Early diagnosis, honest client communication, and timely surgical referral can mean the difference between routine recovery and fatal peritonitis.

By Dr. Geoff Carullo, DVM, FPCCP, DPCVSCA

Sharing this helps others understand what it really means to be a vet. Like and follow if you’re with us.