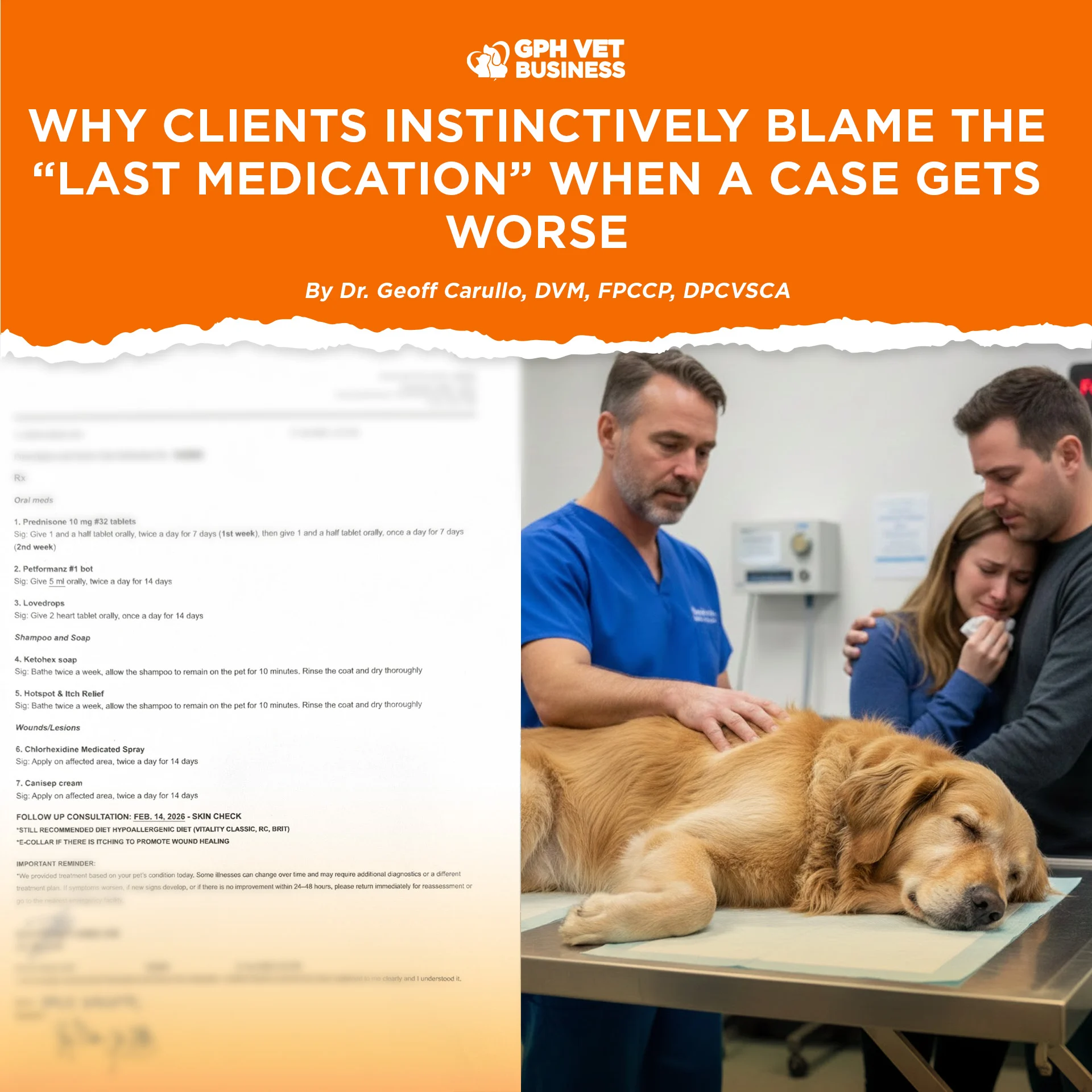

Every veterinarian has lived this moment.

A patient deteriorates.

The case becomes complicated.

Emotions rise.

And almost reflexively, the finger points to the last drug given or the most recent prescription.

“This happened after that medicine.”

“Ever since you gave that drug, lumala na.”

“Maybe the medication made it worse.”

This pattern repeats so often that it deserves a clear, honest explanation. Not defensive. Not emotional. Just grounded in how people think, how disease works, and how veterinary medicine is often misunderstood.

1. Humans Look for a Simple Cause During Stress

When an animal gets worse, clients experience fear, guilt, and loss of control. The human brain reacts by searching for one clear cause.

The most recent medication becomes the easiest target because:

- It is concrete.

- It has a name.

- It happened closest in time to the deterioration.

Progressive disease is abstract. Medication is tangible. So the mind connects the two.

This is not malice. It is psychological coping.

2. Timing Is Confused With Causation

One of the most common logical errors is this:

“It got worse after the medicine, therefore the medicine caused it.”

In medicine, this is a dangerous oversimplification.

Many conditions worsen despite treatment, not because of it:

- Advanced infections

- End stage organ disease

- Neoplasia

- Immune mediated conditions

- Late-presenting cases

The medication did not cause the decline.

The disease timeline simply continued.

But without medical training, clients often equate sequence with cause.

3. Clients Expect Medications to Work Like On-Off Switches

In the client’s mind, medicine often works like this:

- Give drug

- Patient improves

- Problem solved

When that does not happen, disappointment turns into suspicion.

What is rarely understood is that:

- Some drugs slow progression, not reverse disease

- Some treatments are supportive, not curative

- Some conditions are already beyond rescue at presentation

When expectations are not aligned early, blame fills the gap.

4. The “Last Touch” Bias

There is a cognitive bias called last-touch attribution.

The last person or action involved before deterioration is perceived as the most responsible.

That is why:

- The last veterinarian is blamed

- The last medication is questioned

- The most recent decision is scrutinized

Earlier delays, missed signs, late consultations, or poor compliance quietly disappear from the narrative.

5. Guilt Is Quietly Reassigned

This part is uncomfortable but real.

Some clients subconsciously redirect guilt away from themselves:

- Delayed consult

- Declined diagnostics

- Inconsistent medication compliance

- Financial hesitation

Blaming the drug or the veterinarian is emotionally easier than facing the possibility that the disease was already advanced or that timing mattered.

6. Social Media and Google Fuel Suspicion

Online platforms amplify doubt:

“My dog died after this medicine”

“That drug ruined my pet”

“Never trust vets who prescribe this”

Rare adverse events are louder than thousands of successful outcomes.

Clients arrive primed to question rather than understand.

7. Why This Happens More in Progressive and Emergency Cases

You will notice this pattern more often in:

- Critical cases

- Emergency referrals

- Chronic diseases

- Late-stage presentations

Because outcomes are uncertain, emotions are high, and medicine cannot promise certainty.

In contrast, routine cases rarely generate blame because improvement is visible and fast.

8. What Veterinarians Can Do Better (Without Taking the Blame)

This is not about surrendering professional ground. It is about strategic communication.

Before prescribing:

- Explain that deterioration may still occur

- Clarify what the medication can and cannot do

- Document prognosis clearly

- Use phrases like “supportive,” “risk,” and “guarded outcome”

When expectations are set early, blame loses power later.

Final Thought

Blame does not always come from accusation.

Sometimes it comes from fear, confusion, and grief.

Understanding this does not mean accepting unfair judgment.

It means learning how to communicate ahead of it.

Because in veterinary medicine, we are not only treating patients.

We are navigating human psychology during moments of loss.

Sharing this helps others understand what it really means to be a vet. Like and follow if you’re with us.