In the ever-evolving landscape of veterinary medicine, new products often arrive with promises of revolutionizing care. One such contender is nanosilver — tiny particles of silver measured in nanometers, marketed as a powerful antimicrobial that can target bacteria, fungi, and even viruses. From wound sprays to oral supplements, nanosilver has entered the veterinary market with bold claims and glossy packaging.

But despite the marketing hype, many veterinarians remain cautious — even resistant — to using nanosilver as a treatment. The reason is not stubbornness against innovation, but rather a firm commitment to evidence-based medicine, patient safety, and responsible practice.

The Allure of Nanosilver

Silver’s antimicrobial properties are nothing new; ancient civilizations used silver vessels to preserve water and prevent spoilage. Modern science has refined silver into nanoparticles, making it far more reactive and theoretically more effective at killing microbes. Supporters claim that nanosilver:

- Can eliminate a broad range of pathogens

- Prevents biofilm formation in wounds

- Offers an alternative to antibiotics in an age of antimicrobial resistance

On paper, it sounds like a breakthrough. But in the clinic, veterinarians must ask a harder question: Does it truly work, and is it safe for animals?

The Evidence Problem

For any treatment to earn a veterinarian’s trust, it must be supported by strong, peer-reviewed clinical trials — ideally in the same species being treated. In the case of nanosilver, most available data comes from laboratory (in vitro) studies or experiments in non-target species.

While test tubes and Petri dishes may show antimicrobial activity, the jump to real-world veterinary patients is not straightforward. Without large-scale, well-designed in vivo studies in dogs, cats, and livestock, the claims for nanosilver remain unproven in practical veterinary medicine.

Safety and Toxicity Concerns

Silver is not a nutrient; it serves no biological purpose in an animal’s body. In nanoparticle form, silver can enter cells more easily, potentially accumulating in vital organs such as the liver, kidneys, and spleen.

Over time, this bioaccumulation could lead to:

- Argyria — a permanent bluish-gray discoloration of skin or mucous membranes due to silver deposits

- Organ damage

- Unknown long-term toxic effects

With no clearly established safe dosage for pets, the margin between “possibly helpful” and “possibly harmful” is far too narrow for comfort.

Regulatory Loopholes and Quality Issues

Many nanosilver products are marketed as “supplements” or “wellness enhancers” rather than registered veterinary drugs. This allows them to bypass the rigorous testing and approval process required for pharmaceuticals.

As a result:

- Concentrations can vary widely between brands — and even between batches

- Purity and particle size may be inconsistent

- Safety claims may be unverified

This lack of standardization makes it impossible for veterinarians to prescribe nanosilver with confidence.

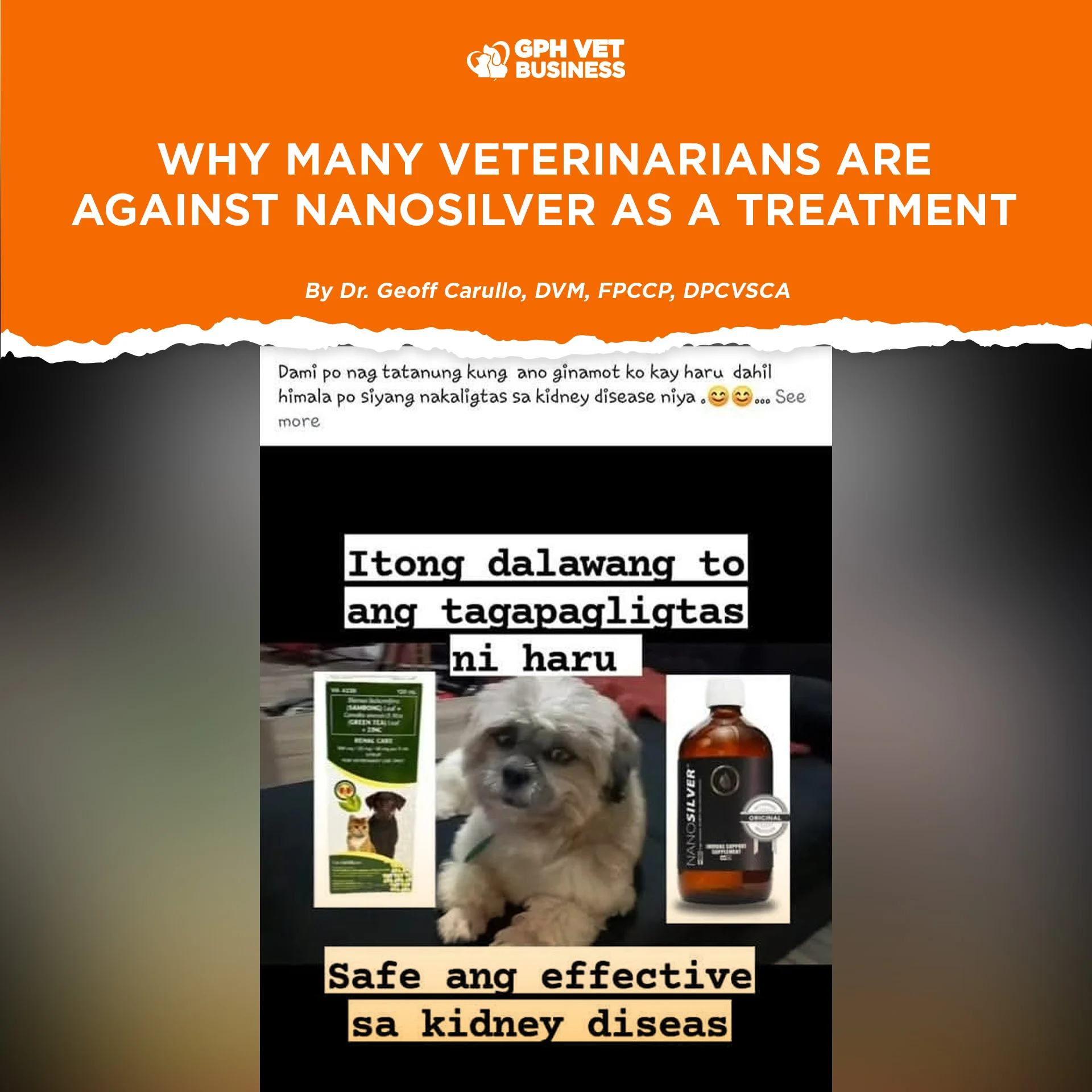

The Danger of Misdirection

Some companies promote nanosilver as a cure for conditions ranging from skin allergies to viral diseases like parvovirus. Such claims are dangerous — not because nanosilver is inherently malicious, but because they delay proven, time-sensitive treatments.

In critical cases like parvo, every hour matters. Choosing an unproven product can cost a life.

Environmental Considerations

Nanosilver does not stop affecting the world once it leaves the patient. Excreted silver particles can enter wastewater systems, disrupt beneficial microbes, and potentially contribute to microbial resistance — one of the greatest challenges in modern medicine.

The Veterinary Perspective

Veterinarians are not against innovation. They welcome progress — but progress must be backed by proof, safety, and accountability.

Without strong evidence that nanosilver is more effective, safer, or more cost-efficient than existing treatments, it cannot be justified as a routine therapy. While some vets may use it in controlled applications such as wound dressings or device coatings, systemic use remains unjustified.

Bottom Line

Until nanosilver meets the same scientific and regulatory standards as established veterinary medicines, most veterinarians will choose caution over risk. In a profession where every decision affects a living being’s welfare, choosing safety is not hesitation — it is duty.

Sharing this helps others understand what it really means to be a vet. Like and follow if you’re with us.