Euthanasia is one of the hardest decisions in veterinary medicine. It is never taken lightly, never done impulsively, and always anchored on compassion, medical facts, and the pet’s overall welfare. While every case is unique, veterinarians follow a set of ethical, medical, and legal guidelines before declaring that euthanasia may be justified.

Below are the core principles most veterinarians use.

1. The Patient Has a Terminal or Irreversible Condition

Euthanasia may be considered when the pet suffers from a disease that:

- Has no known cure

- Will not improve despite available treatments

- Has progressed to a point where survival is no longer medically realistic

Examples include end-stage organ failure, metastatic cancers, severe neurologic deterioration, and irreversible traumatic injuries.

2. Quality of Life Is Severely Compromised

A fundamental rule: When suffering exceeds the patient’s ability to experience comfort, euthanasia becomes a humane option.

Quality of life is assessed through:

- Ability to eat or drink

- Ability to urinate/defecate normally

- Ability to breathe without distress

- Level of mobility or presence of chronic pain

- Frequency of good days vs. bad days

- Level of anxiety, confusion, or distress

If the pet is no longer able to perform basic functions or is living in continuous suffering, euthanasia may be ethically appropriate.

3. Pain or Distress Can No Longer Be Adequately Controlled

Some diseases progress beyond the capacity of medicine to manage pain. If:

- Pain medications no longer work

- The patient requires escalating, unsustainable doses

- The pet is still crying, gasping, or unable to rest

Then euthanasia is considered a humane way to prevent further suffering.

4. Treatment Options Have Been Exhausted or Are No Longer Feasible

Euthanasia may be discussed when:

- All reasonable medical or surgical options have been tried

- Prognosis remains poor despite treatment

- Treatment would only extend suffering without meaningful recovery

This also includes situations where treatment causes more harm than benefit.

5. The Pet Poses a Serious and Unmanageable Welfare or Public Safety Risk

Rare but important situations include:

- Severe, untreatable aggression with documented danger

- Rabies exposure cases, following legal guidelines

- Conditions mandated by public health authorities

These cases follow strict legal protocols.

6. Informed and Voluntary Client Consent

No euthanasia is performed without:

- Clear explanation of the medical status

- Discussion of all possible options

- Signed consent form

- Confirmation that the client understands the procedure and its finality

Veterinarians must ensure that euthanasia is a considered decision, not an emotional reaction.

7. The Veterinarian Must Agree That It Is Ethical and Justifiable

Even if a client requests euthanasia, the vet must evaluate:

- Is the request driven by patient welfare?

- Is the animal truly suffering?

- Is there a realistic alternative?

A veterinarian has the right to decline euthanasia if it violates ethical standards or the patient still has reasonable quality of life.

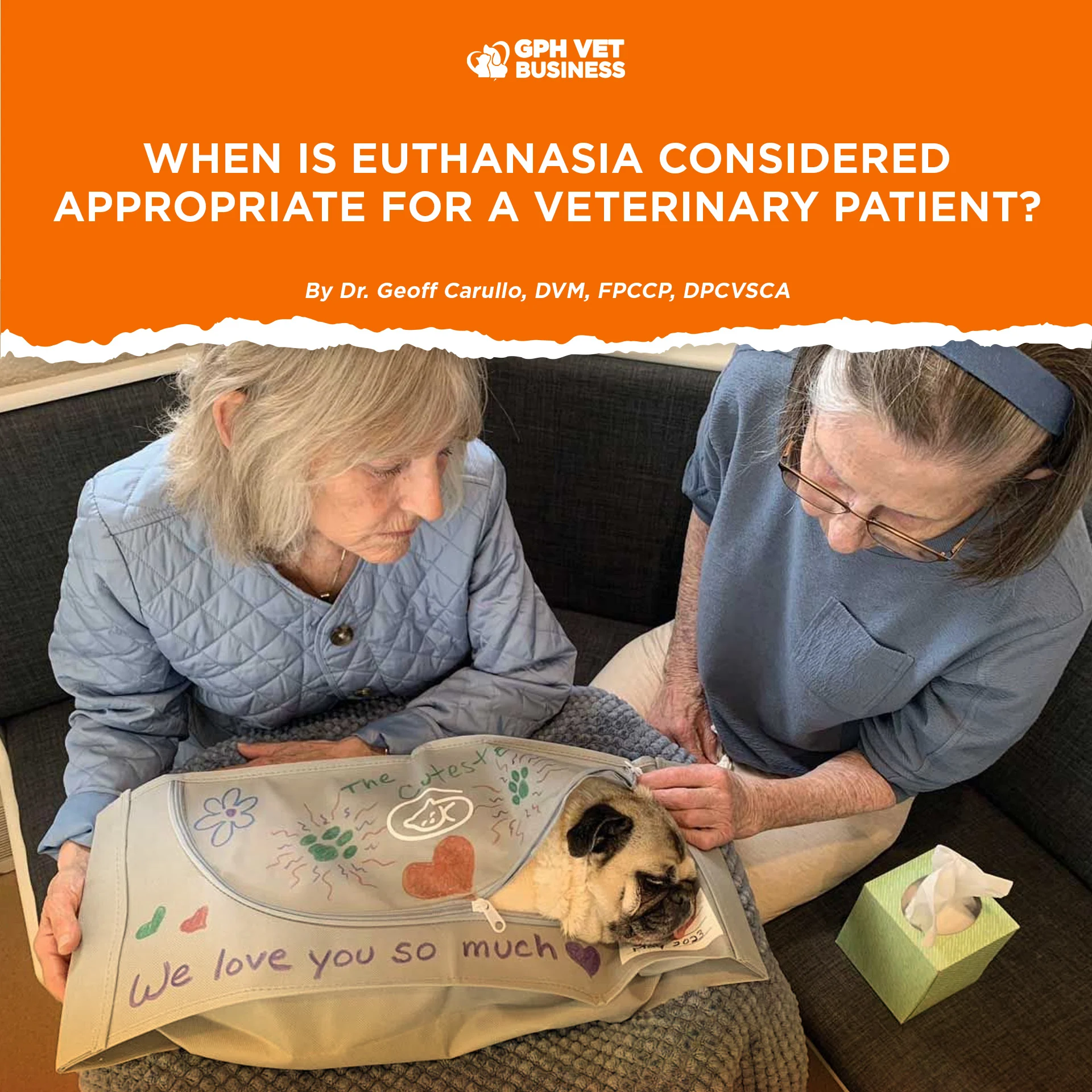

The Heart of the Policy: The Pet’s Welfare Comes First

Euthanasia is not about giving up. It is about ending suffering when healing is no longer possible. It is a final act of compassion — a peaceful goodbye offered when life becomes pain.

Sharing this helps others understand what it really means to be a vet. Like and follow if you’re with us.